Ornamentation in the Music of JS Bach

In this article we will look closely at ornamentation in the music of JS Bach. First we’ll look at some general principles from the baroque era, focusing on rhetoric and the affects. We’ll then take a look at the most important ornaments in the music of J.S. Bach. It is not meant to be an exhaustive treatise on how to interpret or perform all of Bach’s ornaments. Rather, it is only a primer to help get you started. I would encourage you to make your own investigation into the sources. (I’ll list some at the end of the article.) A key consideration is how important the musical context is to understand how to perform it.

Be sure to download the ornaments guide to follow along.

by Dave Belcher

The Purpose of Ornamentation: Rhetoric and the Affects

Rhetoric

In one of the most important treatises of the late Baroque period, Johann Joachim Quantz said that it was the duty of the musician (as it was of the orator) to “make themselves masters of the hearts of their listeners, to arouse or still their passions, and to transport them now to this sentiment, now to that” (On Playing the Flute, 119). The ability of music to “arouse or still” passions, or affects, of the listener is a central theme of Baroque art. Around the Renaissance musicians began to adopt the humanistic approach to rhetoric within the art of oratory (speech). They began to identify, organize, and utilize certain musical rhetorical figures to evoke and stir specific affections in the listener. This grew into an almost systematic and theoretical approach by the time of the late Baroque era.

From speech to music

Decoration or ornamentation was an essential component of this musical rhetoric. In the mid-seventeenth century, German musicologist and theologian Athanasius Kircher said in his Musurgia universalis (1650):

“Our musical figures are and function like the embellishments [colores], tropes, and the varied manners of speech in rhetoric. For just as the orator moves the listener through an artful arrangement of tropes, now to laughter, now to tears, then suddenly to pity, at times to indignation and rage, occasionally to love, piety, and righteousness, or to other such contrasting affections, so too does music through an artful combination of the musical phrases and passages” (5.19).

Affects

How rhetorical figures like ornamentation might move the affects of the listener became important by the time of J.S. Bach. This was the context within which Bach worked and the spirit with which he composed his music.

Martin Luther’s theology of music

Moreover, music’s ability to move the listener’s affects was also key to Lutheran theology in Germany at this time. Martin Luther himself, who had such a huge impact on Bach’s music as a whole, wrote in 1538:

“Music is a mistress and governess [domina et gubernatrix] of those affects [Affectuum] . . . that govern humans or more often overwhelm them . . . For whether you wish to comfort the sad, to terrify the happy, to encourage the despairing, to humble the proud, to calm the passionate, or to appease those full of hate . . . what more effective means than music could you find?”

Bach’s Theocentric Worldview

Preaching and “the Word of God” were central components of Luther’s theology. Thus, he describes music as a “sermon in sound.” As he says, “Next to the Word of God, music deserves the highest praise.” (Preface to Georg Rhau, Symphoniae Iucundae, trans. Ulrich S. Leupold, LW 53:323). Thus, the desired effect music should have in the listener for Bach was both rhetorical and theological. This was true especially of his ecclesiastical works. However, we should note that Bach’s ornamentation was no different between his “ecclesiastical” and so-called “secular” music. That was simply the “theocentric worldview” of Bach’s time. (See Otto Tolonen’s edition of Sonatas and Partitas, 85, trans. Jaakko Mantyjarvi).

From Bach to MLK

We might consider the purpose of Bach’s ornamentation to be like a certain turn of phrase or crescendo in the sermons and speeches of, say, the great preacher Martin Luther King Jr. His namesake was of course the great Reformation preacher. King had a special capacity to “ornament” his speeches in the cadence of his voice. He could take certain proverbial turns of phrases and move his listeners deeply.

Ornament tables

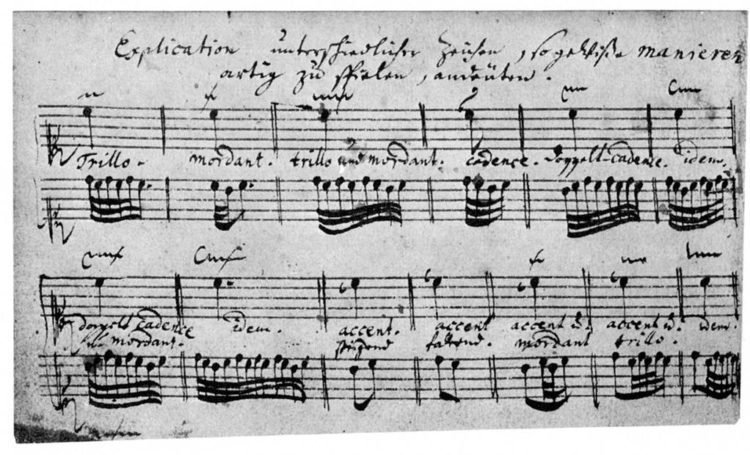

Ornaments (or “graces” as they were more commonly called) refer to the various signs that are used in music for the small diminutions that decorate a melodic or harmonic line. We have become accustomed to the signs Bach used in his ornament table for his son Wilhelm Friederich. However, there are other signs that he used that we do not find in that same ornament table.

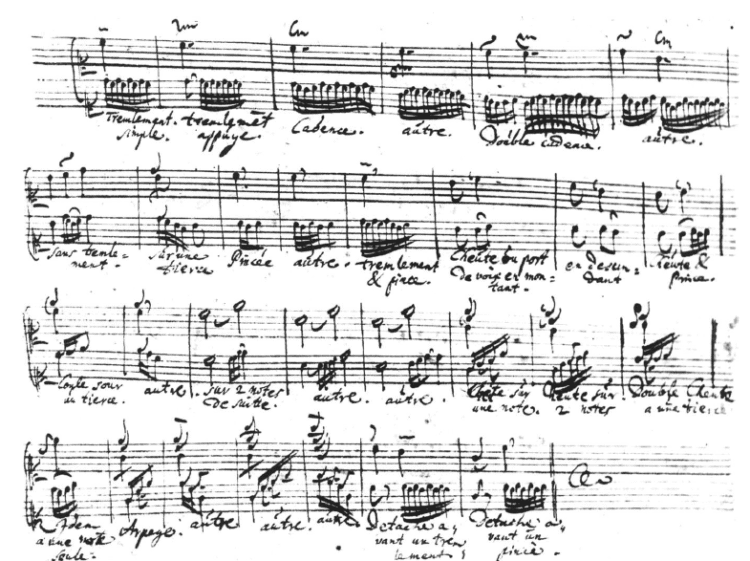

Ornament tables were quite common during the baroque period. Bach’s own ornament table is a shorthand version of a longer version that he copied by hand of the French composer Jean-Henri d’Anglebert (1629-1691).

Take it with a grain of salt

We have to take these ornament tables with a grain of salt, however. They were meant to be more like schemas than precise instructions for how to interpret various ornamental signs. So not only did these tables not include all of the ornament signs one might encounter in a composer’s music of the time but there might be variations in how the composer expected those signs to be performed that differed from the instructions in the table.

Bach’s ornament table

J.S. Bach’s ornament table was titled, Explication unterschiedlicher Zeichen, so gewisse Manieren, artig zu spielen, andeuten. We must remember that it was written for a nine-year old boy and specifically for the keyboard. We will thus have occasion to point out some discrepancies to keep in mind when considering specific ornaments that appear in the table in what follows.

(What follows is not an exhaustive treatise on how to interpret the ornamental signs that appear in J.S. Bach’s music. It is only an introductory primer to help guide you to begin your own investigation.)

Ornaments Overview

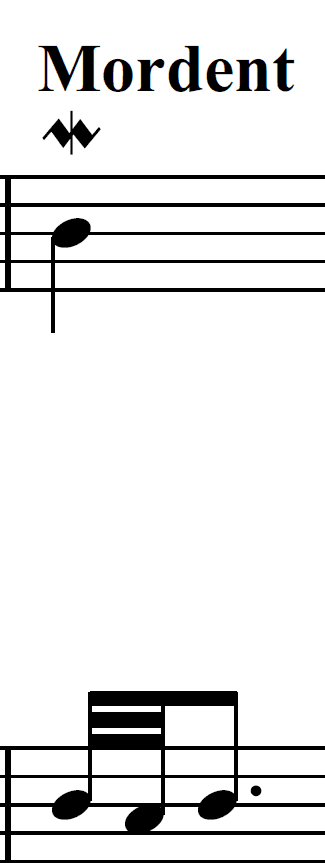

Mordent

- The mordent comes from the word “mordere” in Italian, which means “biting.” A mordent is an oscillation from a principal note down to its lower neighbor and back to the principal note. Some considerations: the mordent has what musicologist Frederick Neumann calls a “penchant for half-tone alternations” in the music of Bach. But there are many instances where diatonic alternations are called for. A semitone alternation out of character with the harmony might clash and so these should be avoided. Mordents often are played on the beat but they can at times be anticipated (or played just before the beat). This will depend on various factors in the musical context. They are not always performed rapidly (in the sense of a “bite”). They can be performed slower in a rhythmic way according to the character of the music. This is especially true in slower movements that feature more recitative melodies. As we will see with many of the ornaments below, mordents often combine with other ornaments to create compound ornaments. The two most common are the mordent-trill (or trill-mordent) and the port de voix et pincé. The latter is an appoggiatura (from below)-mordent.

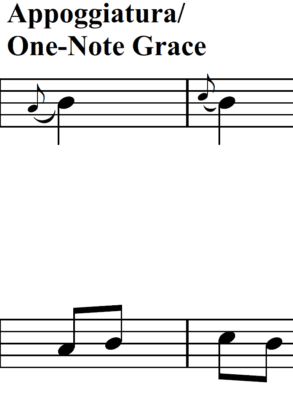

Appoggiatura

- Appoggiatura comes from the Italian “appoggiare,” which means “leaning.” The true nature of an appoggiatura is thus a dissonance (or a non-chordal tone) that leans into its harmonic resolution (a chordal tone). The dissonance is also accented before lightly resolving. However, the term appoggiatura and its symbol (the little note) have been used historically for many other kinds of graces. Thus, Neumann recommends using the term “one-note grace” to avoid confusion. This allows for more specificity with which grace is being used. While an appoggiatura is played on the beat, is accented, and is generally longer (thus taking duration away from the note it’s attached to), a one-note grace might be played before the beat with no accent and have a quick duration that takes much less time from the note it’s attached to. In the case of the Nachschlag it takes value from the previous note!

Some principles for interpreting the appoggiatura in Bach’s music

- There are a number of factors that determine whether you should play a harmonic appoggiatura or a one-note grace. The principal considerations are harmonic and rhythmic. Though, voice leading must also be considered. For instance, if a one-note grace were to create parallel fifths or octaves in the harmony if it were played on the beat, then a pre-beat, shorter one-note grace would be more appropriate than a longer, accented appoggiatura. If the rhythmic and metrical character of the musical context is quick and lively, a longer, accented appoggiatura would be out of place. Thus shorter, one-note graces (whether on the beat or before) would be better suited. Likewise if there is a dissonance in the harmony then a one-note grace that creates additional dissonance would best be played short and before the beat. This prevents a muddying of the harmonic dissonance. In other cases, such as on long, held notes or at cadences, a true harmonic (and thus longer, accented) appoggiatura will be appropriate.

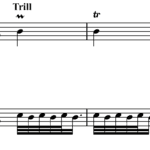

Trill

- A trill can be in one sense almost a species of an appoggiatura (in its true harmonic sense). These kinds of harmonic trills are very closely related to the appoggiatura. Like the appoggiatura, the trill extends the tension the dissonance creates by alternating between the dissonant, non-chordal tone and its resolution. But in another sense the trill can also be very much just a melodic decoration. In these cases it is not meant to be harmonic. Much like a one-note grace, these kinds of trills are equally as numerous as harmonic trills. And, like the appoggiatura / one-note grace, both kinds of trills use the same symbol. (N.B. While Bach uses the squiggly line with chevrons for the trill symbol in the Explication, he most commonly uses the “tr” symbol in the music we often perform on the guitar.) Thus, in essence a trill is simply an alternation of one note with its upper diatonic neighbor. Again — as we might come to expect with all of Bach’s ornaments! — determining which kind of trill we should play will depend on the musical context.

Harmonic trill

- A more harmonic trill that functions like an appoggiatura will have an accent and a slight lengthening of the first note before its resolution. These occur most frequently at cadences. (Cadences were such a frequent place for a trill that in many instances composers would not write a trill symbol at a cadence because they simply expected performers to insert one anyway.)

Melodic trill

- Melodic trills might start before the beat (like a one-note grace) and usually do not have a longer first note. Instead the alternations are much more rhythmically equal. Some trills have a resting point where the alternations should come to an end before the next note. Trills over dotted notes always have a resting point. Dotted-quarter-note trills have a resting point on the third eighth note, while dotted-sixteenth-note trills come to a rest on the third sixteenth. Otherwise the number of alternations in a trill will depend on the musical character of the piece. Faster pieces almost always have very few alternations. Slower pieces (again like pieces featuring recitative) will require more alternations.

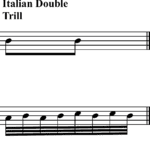

Compound trill

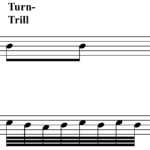

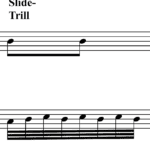

- Compound trills Another consideration to make about trills is that they often combine with musical material both before and after the trilled note to create compound trills. So trills can (and often do!) have prefixes and/or suffixes. The four most common compound trills in Bach’s music are the mordent trill, the slide trill, the turn trill, and the Italian double trill.

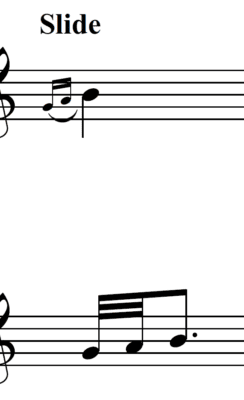

Slide

- The slide approaches a main note by stepping up (or sliding up) from two diatonic notes below the main note. There are three main rhythmic variants of the slide: the Anapest, the Lombard, and the Dactyl. The anapest slide is performed so that the lower auxiliary notes are played just before the beat landing on the main note on the beat, with a slight accent on the first lower auxiliary note. A lombard slide is played on the beat. And the dactyl divides the three notes so that the first note is longer and the last two shorter (such as an eighth followed by two sixteenths). The symbol for the slide does not occur in Bach’s lute suites, cello suites, or violin sonatas and partitas and so you will need to, once again, recognize these rhythmic figures as they appear in the notation. Sometimes the two lower auxiliary notes are written as grace notes preceding the main note, while other times all notes are written in standard notation.

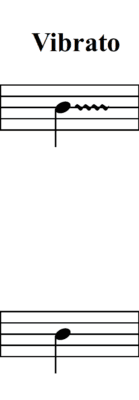

Vibrato

- Vibrato is indeed an ornament in baroque music and it appears in lute literature in particular (as well as in vocal music). On the lute vibrato was performed by rigorously shaking the string up and down (rather than side to side as we do today). It is another ornament that has a symbol in some of Bach’s music but which does not appear in the Explication ornament table. We encounter this symbol in vocal music, but also in one significant place in the violin sonatas and partitas. In the penultimate movement of the Grave movement of BWV 1003 Bach uses the vibrato symbol extending out from a note in the middle of the staff. While some have interpreted the sign as a trill, the very next note that follows it has a trill symbol over it (and this is the same trill symbol Bach uses not only throughout the rest of this movement but throughout the rest of the sonata) and so it is very unlikely that Bach intended this symbol to be a trill. Because vibrato can function in a similar way to a trill — as an intensification of a note, especially of longer notes that might decay easily on instruments like the harpsichord or lute — vibrato is an ornament that was likely used in other places where it is not indicated (again, like the trill).

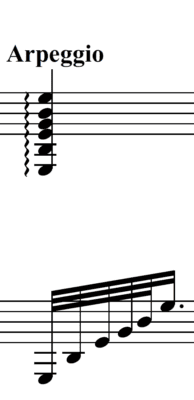

Arpeggio

- The arpeggio is simply a rhythmic division of a chord. In the baroque period block chords were often (especially on the keyboard) rolled into ornamental arpeggiated figures, sometimes highly elaborate ones. While different composers had different kinds of arpeggiation figures, Neumann says that the most common way Bach expected chords to be arpeggiated was a simple roll starting from the bass all the way up to the treble notes. While Bach does use a symbol for the arpeggio (it’s the same as the one we use today in guitar notation) he does not use this symbol in the music we so frequently perform on the guitar. Nonetheless there are many instances where Bach has clearly written out an arpeggio in notation or expects an arpeggio to be added. Fermatas are a prime example where these kinds of ornamented arpeggios are appropriate (and one place Bach writes out an arpeggio in notation would be just preceding the fermata in m.23 of the Prelude to the First Cello Suite, BWV1007).

Turn

- The turn (which Bach in his ornament table calls “cadence“) embellishes a main note with both its upper and lower auxiliaries. Most commonly in Bach’s music the turn starts diatonically above the main note, descends to the main note, and then to the lower auxiliary, and finally returns up to the main note. While the so-called “inverted” turn — starting diatonically below the main note and going up to the main note, above it, and back — does occur in Bach’s music it is much less frequent. In Bach’s music that we commonly play on the guitar — the cello suites, lute suites, and violin sonatas and partitas — the turn is almost always written out in notation. While it is useful to know the sign Bach uses, it is much more important to be able to recognize its rhythmic and melodic form in notation since that is how it usually occurs. (Please note that, while the so-called “inverted turn” is much less common in Bach’s music, it does occur at times — Bach only used one symbol for both kinds of turns, the unfinished figure 8, which can appear either horizontally or vertically in Bach’s manuscripts.)

Wrapping up

Ornamentation in the baroque period is quite complex. The various styles differ so greatly from one another and often commingle in ways that transform one style into something entirely new. From early to mid- to late baroque, from Italy to Germany to France, from composer to composer; it can be quite difficult to get a foothold on just how to interpret the various signs (let alone ornaments that occur written out in notation). The music of J.S. Bach is no different and we encounter a masterful combination of these various styles of ornamentation in Bach’s music that accumulates into a wholly unique style that we can call Bach’s own.

Musical context is key

What makes matters even more complicated is that the best guide to interpreting (and so performing) ornamentation in Bach’s music is that it requires a vast and deep knowledge of the musical context, which means you really do have to take into consideration elements of voice leading, harmony, rhythm, meter, articulation, and melodic function to interpret them well.

Consider your audience

Another consideration to make, though, is that the primary purpose of ornamentation, remember, is to move, to touch the affects of the listener. And so while all of this historical and musical context is very important, as performers we should never lose sight of the audience. Aristotle says in his On Rhetoric that there are three elements that make up rhetoric: the orator, the speech, and the audience. If we forget who we’re performing for and we lose sight of the rhetorical effects our performance of ornaments (and of their connection with everything else in the music around it) might have for our listener, then we also begin to forget Bach’s true purpose with his music.

Resources:

Click on the above link to download a more fleshed-out ornament table of the ornament signs and compound ornaments we’ve discussed above. Please note the rhythms — as with all ornament tables — are rough sketches and not meant to be precise. As we’ve discussed there are many different rhythmic variations for most all ornaments that will depend on musical context.

Most important treatises from the so-called Berlin school:

Johann Joachim Quantz, On Playing the Flute (1752)

C.P.E. Bach, Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments (1753)

Leopold Mozart, School for the Violin (1756)

Other contemporary treatises containing ornament tables and important considerations for ornamentation and baroque music in general:

Jean-Henri d’Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin (1689)

Francois Couperin, The Art of Playing the Harpsichord (1716)

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Treatise on Harmony (1722)

Modern sources:

Frederick Neumann, Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music with Special Emphasis on J.S. Bach (1978)

Stanley Yates, ed., J.S. Bach: Six Unaccompanied Cello Suites Arranged for Guitar (1998)

Frédéric Zigante, ed., Johann Sebastian Bach: Complete Lute Music (2001)

Frank Koonce, ed., Johann Sebastian Bach: The Solo Lute Works, 2nd ed. (2002)

Jerome Carrington, Trills in the Cello Suites: A Handbook for Performers (2009)

Timo Korhonen, ed., J.S. Bach: Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, trans. Jaakko Mäntyjärvi (2011)

Frank Koonce and Heather DeRome, eds., Johann Sebastian Bach: Sonatas & Partitas: Six Violin Sonatas Arranged for Guitar (2019)

The ornamentation article is Excellent! Great explanations and description(s).

[…] Ornamentation in the music of J.S. Bach […]

Thanks very much Dave for this interesting article! I liked it a lot!