Guest post by Jeff Peterson

There is a wealth of great music written or transcribed for the classical guitar that spans hundreds of years from the Renaissance era to the present day. The ukulele was developed from the Portuguese braguinha in the 1880s which is a relatively short time after the modern guitar evolved with the brilliant work of Antonio de Torres Jurado in the 1850s-70s. Despite this, there is a very limited amount of classical music published for the ukulele. Some music was composed and published in the early 1900s by Ernest Ka’ai and more music was arranged and composed over the past thirty years but there is still a limited range of classical music available.

A logical source for more music for the ukulele is from the classical guitar repertoire. This gives ukulele players wonderful new music to explore at all playing levels and also gives classical guitarists a very good head start learning the ukulele. Both instruments can be played with similar right and left hand techniques but have unique and distinct voices that make playing classical repertoire on both very satisfying to players and listeners alike. To take a deeper dive into playing classical music on ukulele, check out this article I wrote for Ukulele Corner.

This brings up the exciting challenge of arranging classical guitar music for the ukulele. Many decisions can be made in the process to best serve the music of an instrument with half the range of the guitar and a higher register. Here are some of the things to consider that can make a seemingly impossible transition between the instruments very natural:

- Range

- Right and Left Hand Fingerings

- What aspects are essential in the music and what can be left out

- How to achieve the most sustain and bring out dynamics/expression in the music

- What is possible on the ukulele that would be difficult or impossible on the guitar

- Can techniques that are common on the ukulele but not common on the guitar be used

- High G (re-entrant) tuning fingerings

The first step in the arranging process is often to look at the range of the melody and accompaniment. With the limited range of the ukulele certain solo pieces can immediately be ruled out. A good example of this would be La Catedral by Austin Barrios Mangoré. Essential elements of each movement of the three-part suite move beyond the range of the ukulele and don’t work when changing melodic lines to different registers and keys. I see pieces like these as potential duets between ukulele and guitar (or other accompanimental instruments). A guitarist can test pieces by reading them as if playing the top four strings of the guitar. With the low G tuning all the music will sound the interval of a fourth higher on the ukulele. With the re-entrant tuning any notes on the fourth string will sound an octave plus a fourth higher. Some pieces will immediately fall into place and can work on the ukulele with few if any changes.

Here are a few examples:

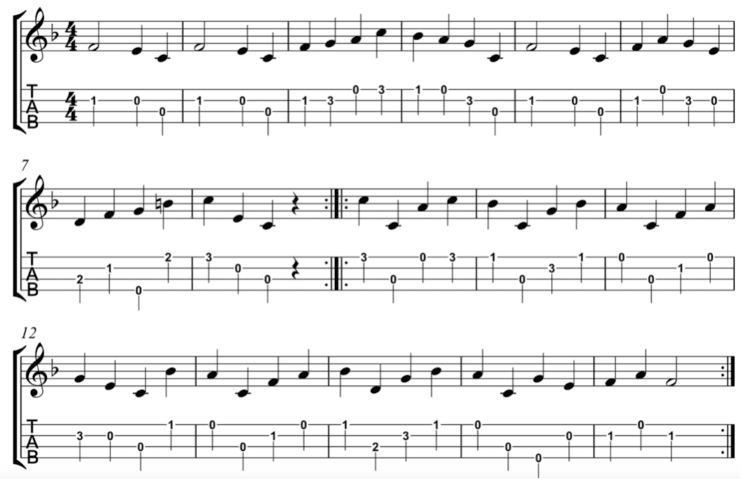

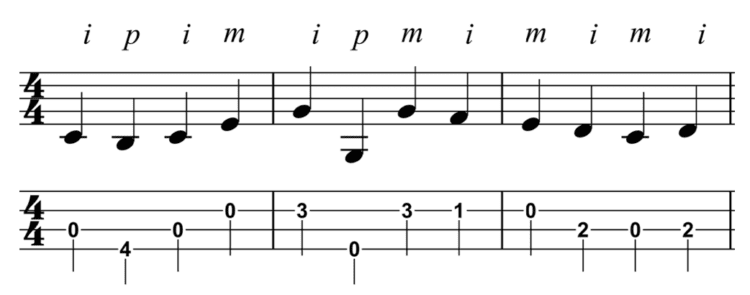

Fernando Sor Little Study

Aguado Estudio #1

The notes fall in a comfortable range in both these examples when played with the same fingerings as on the guitar. The Sor Study is transposed from C to F. The note G in bar 15 uses the 4th string in the re-entrant high G tuning but could be played on the 3rd fret of the 2nd string like the original. The Aguado Estudio is transposed from Am to Dm. The same right and left hand fingerings work perfectly.

Here is an example of a piece that still fits in the range of the Low G ukulele but fingerings are changed to better serve the music and to aid in playability:

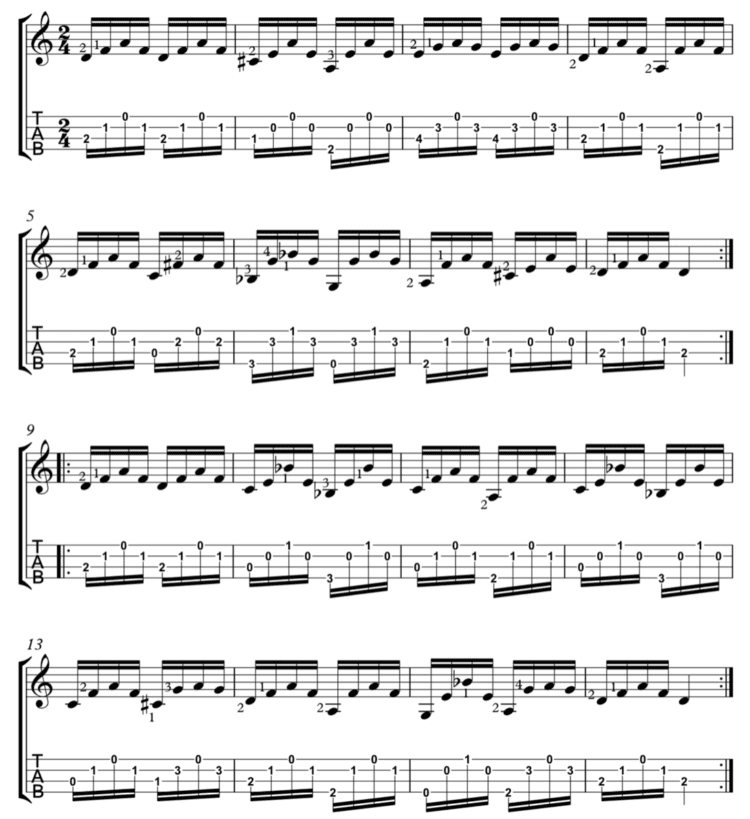

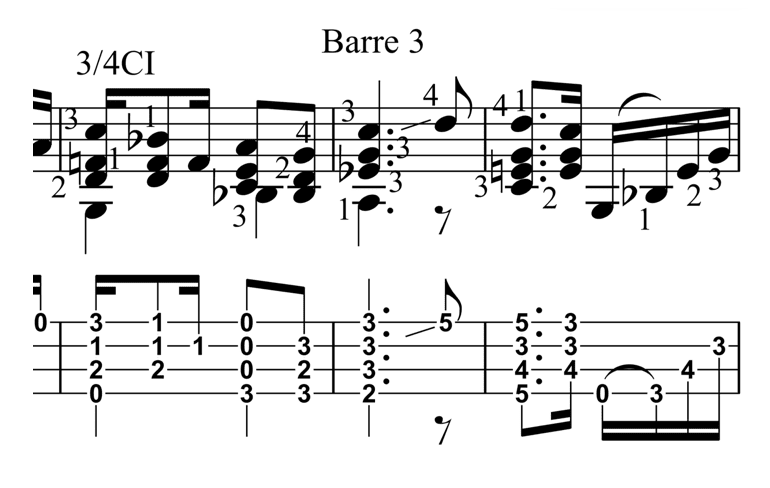

Francisco Tárrega Lágrima (measures 5-8)

The left hand fingerings in measure 5 are changed but the notes are played at the same frets as on the guitar. Barre chords are avoided and the 2nd finger stays in place on the 3rd string. The three note chord at the beginning of measure 5 would be a very difficult stretch on the guitar but works with relative ease on the ukulele allowing a smooth connecting of notes with out the challenge of high position barre chords. Also in this line, the fingerings are moved in measure 6 on beats two and three using open strings for sustain.

Here is and alternative fingering for measures 7 and 8 which also works well and does not require a position shift in measure 8. Note that the ending bass notes are moved up an octave from the original due to the limited range of the ukulele. This movement does not affect the flow and balance of the music.

In measure 11 the phrase containing large interval jumps can be played with overlapping notes for sustain on the ukulele with stretches that would not be possible on the guitar. The phrase is played all in 7th position on the guitar but moves down the neck leaving out the sustained bass note on the ukulele. The F# played with the left hand fourth finger can sustain into the B on the fourth string by reaching with the first finger and allowing overlap for a moment.

Listen to the difference between “Lágrima” on ukulele and classical guitar.

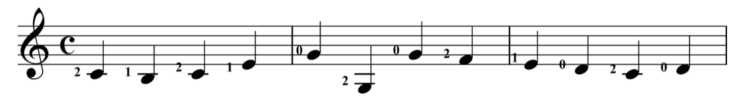

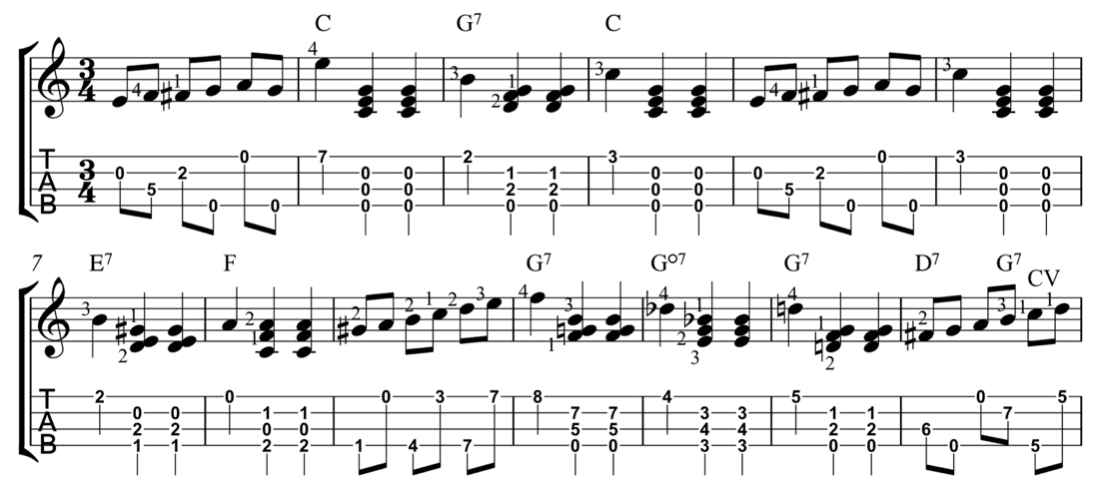

It is also possible at times to read and re-finger a piece for guitar in the original key. Here is an example from Study No 3, Op. 60 by Fernando Sor:

Guitar phrase and fingering:

Ukulele re-fingering:

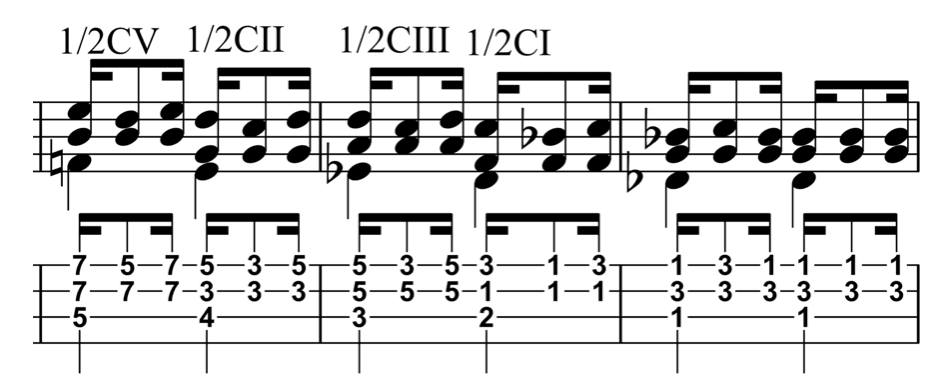

Many techniques that are common on the ukulele can be used to interpret pieces from the classical guitar repertoire. One technique is creating barre chords with the second, third, or fourth fingers. Here is an example of a third finger barre chord in Choros No.1 by Heitor Villa Lobos:

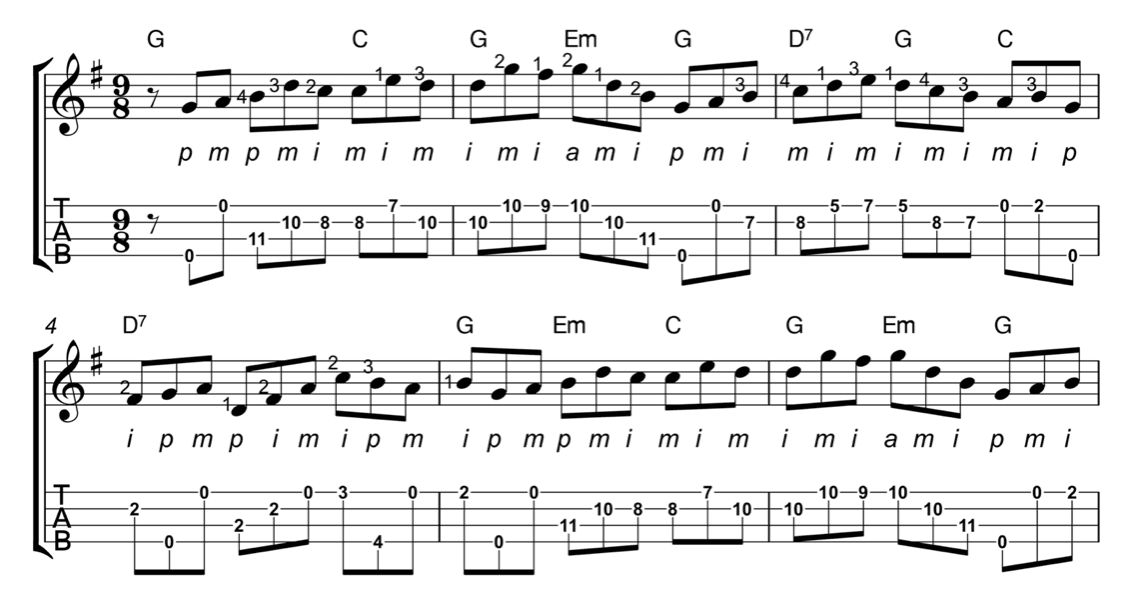

Campanella fingerings which combine fretted notes with open strings also work well on ukulele using both types of tunings. The example of Lagrima demonstrates this technique using a low G tuning. The re-entrant high G tuning offers many other possibilities:

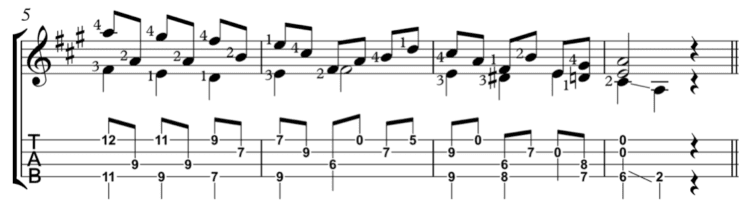

J.S Bach Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring(first theme)

Ernest Ka’ai Hone A Ka Wai excerpt arranged from the original published music using campanella fingerings with the high G tuning

Measures 1, 5, 9, and 13 use combinations of movement mainly between the 4th

and 1st strings to create stepwise motion that can overlap in each position for sustain.

Another thing to consider is what is essential to keep and what can be left out when there are more notes or impossible voicings. Essential elements are the melody and overall harmony of a composition. Bass notes often can be moved, different chord inversions can be used, and smaller chord voicings can be used that still give the essence of a passage. An example is measures 25-27 in Choros No.1 by Heitor Villa Lobos:

The original score has full 6 note chords. The notes on the top three strings still bring out the melody, harmony, and rhythmic motion of the passage. Bass notes could be added on the 4th string with a low G tuning on downbeats but moving the downbeats to the 3rd string adds more clarity on the ukulele.

It is a wonderful experience finding the perfect fit for a classical guitar piece on the ukulele. Many pieces that may seem unlikely to work including Choros No.1 by Villa Lobos and Capricho Arabé by Tárrega are not only playable with slight modifications but are a great joy to perform. This mirrors the development of the modern classical guitar repertoire which borrowed from abundant sources including Bach’s lute and cello suites and Spanish piano music by Isaac Albéniz and Enrique Granados. A similar process of transcriptions will allow the limited repertoire of classical ukulele music to evolve bringing centuries of wonderful music to life with a new voice.

(Ukulele Corner offers a graded repertoire series transcribed, fingered, and arranged by Jeff Peterson drawing from Renaissance, Classical, Romantic, and Modern Era composers.)

All music from this article is available in Jeff’s book Graded classical music for Ukulele

I loved this article! I’ve been spending several hours each week with an ukulele ensemble. Mostly we’ve been playing folk, country & western, and pop music with accessible chords. I’ve tried introducing some classical work (Pachelbel’s Canon for example). Most use standard ukulele tuning, but we do have a baritone ukulele tuned like a guitar, and my ukulele has low-G tuning. Lot’s of fun.

I will definitely be looking into Jeff’s book.

Steve

I just finished spending the past month on learning chords and notes for the Baritone tuning of the ukelele…EBGD and did not realize this book was for low G tuning. How did I not see that. Love the pieces but now…what is the best way to adapt besides never opening the book to avoid the frustration. I do not want to retune the strings and relearn as this messes too much with my head. Suggestions please.

Also it would be a real help to put the chords on the music pieces for those musicians who want to accompany others that are playing the main part. I can see this book would be useful for mandolin players where the tuning is EADG