Key Signatures in Classical Guitar Music

Key signatures in music tell you either how many sharps or how many flats to play throughout a section or piece of music. A key signature will always consist of either sharps or flats, never both. You may hear musicians talk about playing in “sharp” keys or “flat” keys. This is a reference to a piece of music’s key signature. And all of this applies to every piece of classical guitar music you’ll read. At the end of the article we’ll look at why some keys are more common on the guitar than others. Let’s dive a bit deeper.

Here are the topics we’ll cover — click any topic to skip to that section of the article:

- Location of Key Signature

- Meaning of the Key Signature

- How to identify what key a piece is in

- Minor Keys and their relationship to Major Keys

- The Circle of Fifths

- Naturals in the Key Signature

- Weird Keys

- Common Keys on Classical Guitar

Where is the key signature on a score?

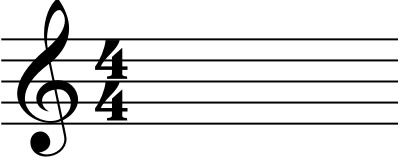

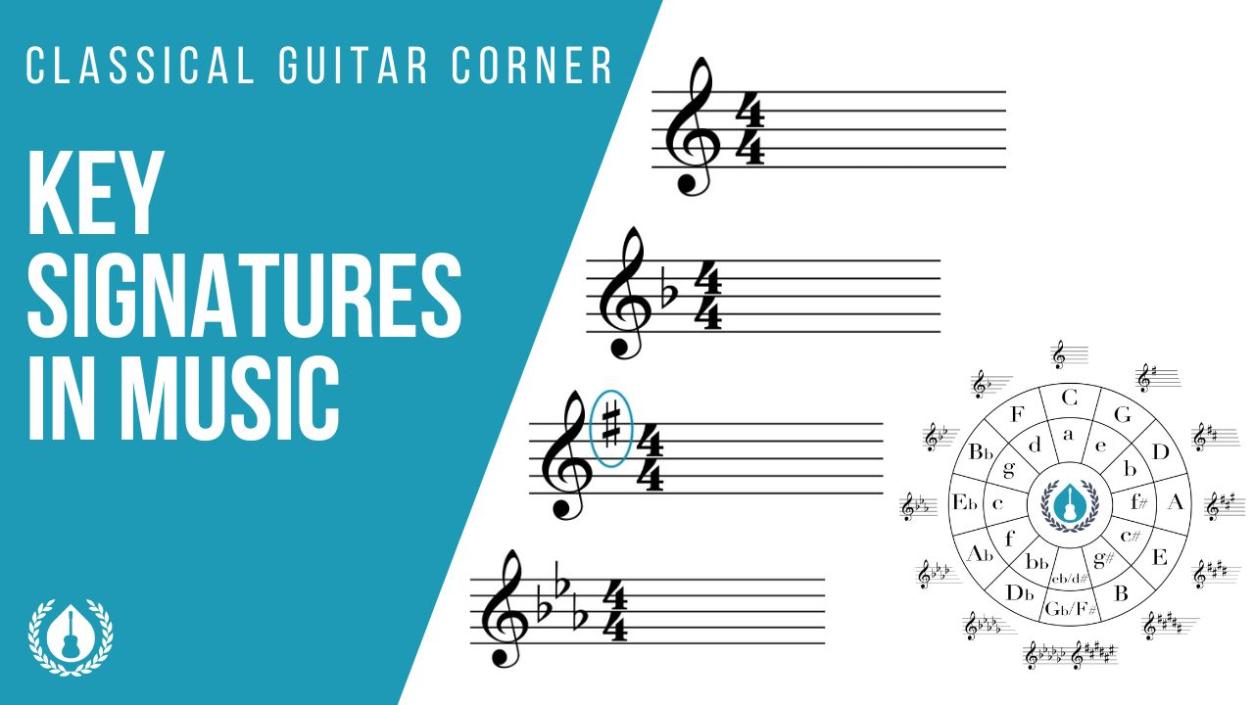

First off, where can we find the key signature? It is always located after the staff symbol and before the time signature. Usually this is pretty straightforward, but there are two keys (C Major and A minor) that don’t have any sharps or flats.

First off, where can we find the key signature? It is always located after the staff symbol and before the time signature. Usually this is pretty straightforward, but there are two keys (C Major and A minor) that don’t have any sharps or flats.  So if you see a staff symbol and time signature right next to one another with nothing between, this is a good clue to what key you’re in. However, all other key signatures will be located between the staff and time signature symbols.

So if you see a staff symbol and time signature right next to one another with nothing between, this is a good clue to what key you’re in. However, all other key signatures will be located between the staff and time signature symbols.

What does the key signature mean?

A key signature tells you what key a section or piece of music is in. Every key has a specific set of whole and half steps that make up a particular scale. The C Major scale for instance, follows this formula starting on the note C. And that means there are no sharps or flats in this key. If we use the same formula starting out on the note G, however, we end up with one sharp. Below we’ll talk about why some keys use sharps and others use flats, but never both.

How do I identify what key a piece is in?

So how can you always know what key a piece is in? In short, how do I crack the code of the key signature?! Let’s start by looking at the order of sharps and flats. Once you know that, there is a simple formula for figuring out what key a piece is in every time.

The order of sharps in a key signature

Every key signature follows a specific order of either sharps (#) or flats (♭), from left to right. Sharp keys follow this order:

F-C-G-D-A-E-B

And we can always discover the key of a piece of music with sharps in the key signature with a simple formula. Take the last sharp (furthest to the right) in the key signature and raise it one half step. That’s your key.

So, for instance, let’s use our example above of one sharp (F#). Raise that one half step and you get G. So one sharp is the key of G Major. Or let’s say you have four sharps (F-C-G-D). The last sharp is D# and one half step above that is E. So four sharps makes the key of E Major. Simple, right?

So, for instance, let’s use our example above of one sharp (F#). Raise that one half step and you get G. So one sharp is the key of G Major. Or let’s say you have four sharps (F-C-G-D). The last sharp is D# and one half step above that is E. So four sharps makes the key of E Major. Simple, right?

The order of flats in a key signature

Flat keys work a little differently. But, first, let’s take a look at the order of flats from left to right:

B-E-A-D-G-C-F

You may notice that flats are exactly the same order as sharps, just in reverse. And just like with sharps, there is a simple formula to help you figure out the key. However, it’s different than it is with sharps.

The next to last flat (the one second from the right) will tell you the key.

So, for instance, let’s say you have three flats (B♭-E♭-A♭). The key of the piece will be E♭ Major (next to last flat). Easy! There is one exception to this rule, however.

So, for instance, let’s say you have three flats (B♭-E♭-A♭). The key of the piece will be E♭ Major (next to last flat). Easy! There is one exception to this rule, however.

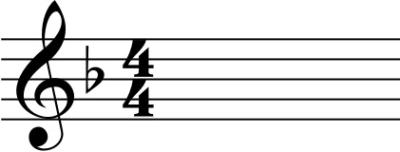

If you have only one flat (B♭), there is no “next to last flat” — that B♭ is the one and only flat. In that case we have to think about the order of flats as a cycle. When we get to the end of the order of flats we go back to the beginning. So in this case, the next to last flat of B♭ is F♭. But this one is tricky and the true exception to the rule. The key is not in fact F♭, but F Major. So you’ll need to just memorize this one: one flat (B♭) is F Major.

If you have only one flat (B♭), there is no “next to last flat” — that B♭ is the one and only flat. In that case we have to think about the order of flats as a cycle. When we get to the end of the order of flats we go back to the beginning. So in this case, the next to last flat of B♭ is F♭. But this one is tricky and the true exception to the rule. The key is not in fact F♭, but F Major. So you’ll need to just memorize this one: one flat (B♭) is F Major.

Three flats is a really common key, because it is the same key signature for C minor. (Below we’ll talk about why this and other flat keys are much less common on classical guitar, however.) But, hang on (I can hear you saying), we just said it was Eb♭ Major, so how can it also be C minor?! Well, as it turns out, every key signature has two keys: the Major and the minor.

Minor keys and their relationship to major keys

Every Major key has what is called a “relative” minor (and vice versa). We already noted above that the key signature that has no sharps or flats is both C Major and A minor. And the reason is that these are relative keys.

Remember above we talked about how the Major scale follows a particular formula of whole and half steps? Well, the minor scale also has its own formula. (Go here to get access to our ultimate guide to scales, including major and minor scale formulas.) When we apply the minor scale formula to the sixth scale degree of the Major scale, we end up with the relative minor scale. That might sound complicated, but it’s really simple. Let’s break it down.

In the key of C Major, all we have to do to find the relative minor is to start on the sixth scale degree. Here are the scale degrees of C Major: C-D-E-F-G-A-B. So the sixth scale degree is A. And the minor scale formula follows a specific pattern of whole and half steps, like this:

W-H-W-W-H-W-W

An even simpler way to do this, though, is to stick with the Major scale formula, just starting on the sixth scale degree.

And this works in reverse as well. If we’re in the key of A minor, we can always find the relative Major by starting on the third degree of the minor scale. Here are the scale degrees of A minor: A-B-C-D-E-F-G. So the third scale degree is C.

Yeah, but can I have a cheat sheet? The Circle of Fifths

We talked above about how there are “sharp” keys and “flat” keys. These derive from something called the “circle of fifths.” This is a handy tool that shows you all 24 possible key signatures. This includes Major and the relative minor keys. The circle is arranged so that you follow the order of sharp keys if you go clockwise around the circle. And when you go counter-clockwise around the circle you move through all of the flat keys. It’s called the circle of fifths because as you go clockwise around the circle you move up an interval of a fifth. So C up to G is a fifth, while C down to F is also a fifth.

We talked above about how there are “sharp” keys and “flat” keys. These derive from something called the “circle of fifths.” This is a handy tool that shows you all 24 possible key signatures. This includes Major and the relative minor keys. The circle is arranged so that you follow the order of sharp keys if you go clockwise around the circle. And when you go counter-clockwise around the circle you move through all of the flat keys. It’s called the circle of fifths because as you go clockwise around the circle you move up an interval of a fifth. So C up to G is a fifth, while C down to F is also a fifth.

While it’s good to learn all of the tricks we have shown you throughout this article to learn your keys, the circle of fifths gives you an easy cheat sheet. Download a free Circle of Fifths diagram here.

Natural symbols in the key signature?

Let’s look now at one unusual key signature you may see in your music. Sometimes a section of music may have natural symbols.

That first word “sections” is really important here. You will pretty much never see an entire piece with natural symbols in the key signature (at least we’ve never seen one). What you will see is natural symbols in a key signature at the start of a new section. And this pretty much always signals a key change.

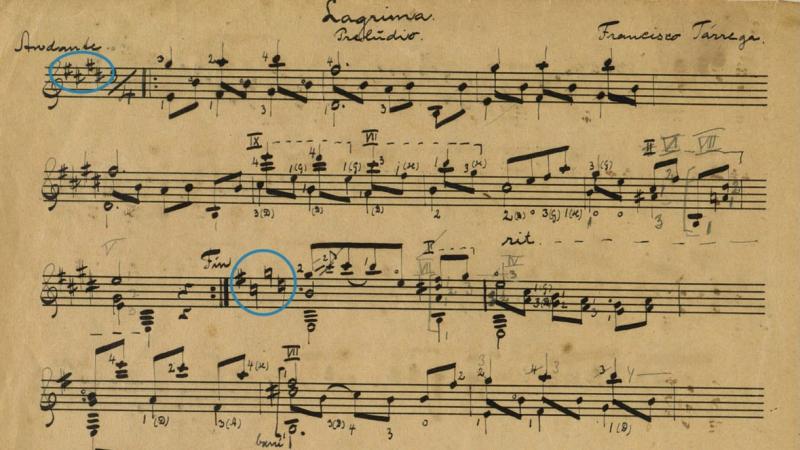

Here’s a great example from the classical guitar piece “Lágrima” by Francisco Tárrega. Notice how the first section begins with four sharps (that’s E Major!), but the second section begins with one sharp and three natural symbols. This means the last three sharps (C-G-D) have all become natural, leaving us now with only one sharp. And that changes the key from E Major to E minor.

So always be on the lookout for natural symbols at the beginning of a new section. It’s pretty much always signalling a new key!

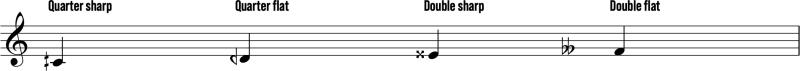

Weird Key Signatures

While it is possible to see quarter tones or possibly double flats or sharps in a key signature, it would be exceedingly rare in guitar music. (See our article on accidentals in music for more on these.) But here are what they look like:

A context where these might pop up in notation would be microtonal pieces or in Eastern and Middle Eastern music. For instance, music on the oud — a fretless, lute-like instrument from Persia — would need quarter tones to denote some of the pitches in music notation.

Common Keys on Classical Guitar

One thing you’ll discover is that classical guitar music doesn’t feature too many pieces in, say, Gb Major or Db Major, while these are much more common in piano music. And there’s good reason for this. The left hand is limited in its reach and its strength and flexibility. For that reason, we really need open strings both to avoid too many barre chords (which quickly tire out the hand) and to create more fingering options.

However, flat keys tend to have many fewer open string options than do sharp keys. For instance, E Major has four sharps, with the possibility of at least four open strings. Ab Major, however, which has four flats only has one open string. Go here to learn much more about common keys on classical guitar.

***

We hope this deep dive into key signatures has been useful for you and that you now feel confident in deciphering what key your music is in!

Leave A Comment