Rubato in Classical Guitar Music

One of the more elusive concepts for beginners and intermediates alike is how to apply rubato in classical guitar music. But before we arrive at the practice we first need to understand the theory behind rubato. What exactly is it (and what is it not)? When is it appropriate to use and when not? How do we do it? And how do we measure a successful application of rubato?

What is rubato?

Music in time

According to a popular definition, music consists of two aspects: pitch and rhythm. Thus, music exists in time. A piece of music typically has a time signature (and meter), a specific tempo (or range of tempos), and a dialogue between rhythm and silence. So how do we measure musical time?

Once we understand how many beats of what kind there are per bar (time signature / meter), and combine that with an understanding of tempo, we can count more or less “in time.” And while humans have a pretty good sense of time, we are not perfect. We may count a beat a little early, the next a little late, and so on. So the easiest way to measure time precisely is the metronome.

The metronome

The metronome is a nineteenth-century invention that precisely divides time into a specific number of beats per minute. In that sense, it is a “true” representation of tempo. Modern metronomes usually have Italian tempo markings next to a range of tempos that supposedly fit each term. We can play “with” the metronome, essentially training our sense of time to be more in sync with the metronome’s (more precise) sense of time.

But most agree that playing too much like a metronome sounds “wooden” or “robotic” (read: metronomic). Another way of putting that is: playing too much like a metronome lacks all human expression. In this view, we need to temper a need to correct our imprecise sense of time with our very human sense of an expression of time. Here’s where rubato comes in.

Stealing (and giving back) time: The Honorable Theft

Rubato comes from a broader term, “tempo rubato,” which means stolen time in Italian. Our modern idea of rubato is that we “steal” time by broadening tempo and any amount of time we steal must be given back by speeding back up (or vice versa). And according to a popular opinion, we get this form of expression from the Romantic period. In fact, according to some modern interpretations, rubato was foreign to baroque music, which should be played “strictly in time.” And it should be used only sparingly in Classical-period music.

However, the term first comes into use in the 18th century. In 1723, Pier Francesco Tosi writes in his Opnioni de’ cantori antichi (Observations on the Florid Song):

Chi non sa rubare il Tempo cantando, non sa comporre, n’e accompagnarsi, e resta privo del miglior gusto, e della maggiore intelligenza.

He who does not know how to steal Time by singing, does not know how to compose, nor how to accompany himself, and remains deprived of the best taste, and the greatest intelligence.

According to Tosi, this rubato is an “honorable Theft” so long as the singer provides “Restitution with Ingenuity.” So this is actually where we first encounter the idea that tempo rubato is a stealing and giving back of time, in the Baroque period.

Tempo Rubato

And the term tempo rubato is also one we find in all of the members of the Berlin School, transition figures between the Baroque and Classical periods: C.P.E. Bach, Leopold Mozart, and Johannes Quantz. Emmanuel Bach suggests that “Most keyboard pieces contain rubato passages.” In other words, it was not something used only sparingly in eighteenth-century music, but was happening all the time. His definition? The left hand was to keep strict time while the right hand allowed for expressive manipulations of time.

You may have heard this definition applied to the music of Chopin (who discussed the principle frequently), but its provenance is much older. None other than W.A. Mozart, in a letter in 1777, mocked those musicians who allowed the left hand to “follow suit,” “giving in” to the changes of tempo in the right hand. In other words, the overall tempo would fluctuate, instead of just the melody. People marveled at Mozart’s ability to keep the left hand steady while changing time at will in the right.

“Earlier” and “later” rubato

Roger Hudson in his book Stolen Time calls these two approaches to rubato: “earlier” and “later.” The “earlier” form asks for a steady maintenance of pulse in the accompaniment while the melody is free and “against the bar.” In contrast, “later” rubato is an overall expressive fluctuation of tempo (what Mozart lamented). Applied to the keyboard, this would mean both hands express the manipulation of time together.

Even in C.P.E. Bach’s account, however, Mozart’s, and later Chopin’s, ideal of hand independence is quite difficult for the keyboardist to perform. Thus, Bach suggests: “Other instrumentalists and singers, when they are accompanied, can introduce the tempo much more easily than the solo keyboardist.” Which is to say, being expressive with the tempo of the melody while keeping the accompaniment in strict time is much easier in an ensemble setting. Eventually this would also become the dominant approach of soloists as well. We’ll return to how difficult this is on guitar below.

“…for feeling also has its tempo.”

This is a quote from the inscription of Beethoven’s 1817 song, “Nord oder Süd” (WoO 148). By this time Beethoven was using metronome indications in his scores. This song does bear a metronome marking, but he notes that it only applies “to the first few measures, for feeling also has its tempo.” Another term for Beethoven’s tempo feeling or expression that would come to dominate the practice of the later nineteenth century was “agogic” rubato.

Agogic phrasing allows for some notes to be longer or shorter than their written duration for expressive effect. In Beethoven’s time, notational conventions had not yet developed for agogic rubato. But that would change with Franz Liszt.

The heroic self-expressive individual

Liszt was notorious for writing in many different expression markings for slowing and speeding up the tempo. But he also started to use new signs that indicated a flexibility of tempo’s feeling as well. Liszt’s approach to time as both a performer and composer changed the landscape for the “feeling” of tempo and still impacts our understanding of “rubato” to this day.

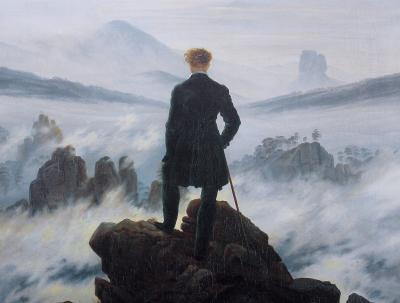

The basic idea of this Romantic approach to feeling is the self-expression of the composer and/or performer. Music becomes a vehicle for the individual who stands out against nature. The classic example of this self-expression and reflection, of the subject against nature, is Friederich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). The heroic individual stands atop a precipice overlooking a natural landscape below. The painting centers on the human subject and all lines point back toward this individual. In a musical setting, tempo (and all other musical elements) become subject to the individual composer or performer and their expression.

The basic idea of this Romantic approach to feeling is the self-expression of the composer and/or performer. Music becomes a vehicle for the individual who stands out against nature. The classic example of this self-expression and reflection, of the subject against nature, is Friederich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). The heroic individual stands atop a precipice overlooking a natural landscape below. The painting centers on the human subject and all lines point back toward this individual. In a musical setting, tempo (and all other musical elements) become subject to the individual composer or performer and their expression.

The “abuse” of rubato

And that brings us to today and to the guitar. The general consensus is that Liszt represents this latter Romantic understanding of the self-expressive performer. Thus, he is held responsible for modern-day “abuse” of rubato. As we have seen, however, there is a complicated history behind Liszt and perhaps things are not so cut and dry. The guitar’s history is caught up with this same history and developed alongside these changing understandings of tempo throughout the Baroque, Classical, and Romantic eras.

There is no question that the modern guitar inherits a Romantic spirit present in so much Spanish music. But it would be incorrect to say it only inherits this Romanticism. There is both “earlier” and “later” rubato in the guitar’s history, and different players utilize different approaches. We are lucky to have such a rich history that is represented by so many gifted composers and performers on the guitar. We will talk about how “rubato” can be abused, but it is not at all as universally true today as some claim.

Rubato on the guitar

“Earlier” rubato on guitar

Let’s look first at Hudson’s “earlier” rubato. Is the “earlier rubato” of C.P.E. Bach, W.A. Mozart, and Chopin even possible on the guitar? Take, for instance, the example of the Spanish Romanza. It has a clear quarter-note melody on top over a triplet accompaniment underneath. Keeping a strict triplet accompaniment pulse while modifying the tempo of the melody, even one so simple, is a monumental technical task. Give it a try: it’s much, much harder than you might think.

“Later” rubato on guitar

Most all guitarists thus use what Hudson calls “later rubato.” Here the tempo fluctuates to allow the music to breathe. But, especially given the reputation guitarists have for being too flexible with tempo fluctuations, when should we use rubato?

We have seen above that it is a bit of a myth that Renaissance and Baroque music should be played strictly in time, while Romantic music should be more flexible with time. So the real question is not about whether rubato is okay in earlier music, but how much is too much.

How much is too much?

And here’s where we start to encounter some controversy. It is true that many guitarists can use the principle of rubato, fluctuating tempo, to cover over bad rhythmic habits. Essentially, we are guilty of using it too much of it and apply Romantic ideals of musical expression in a blanket way, instead of stylistically. And it is also true in general that Romantic music should have a greater degree of rubato than earlier music. Remember, Bach (and later Mozart and Chopin) tell us that the left hand keeps strictly in time as the right hand is free. What this means is that the overall tempo does not change in Baroque and Galant music. At least this is true as an ideal to strive for.

But how do we balance this using only “later” rubato? Here are some examples so you can hear how time is stretched in more subtle and more dramatic ways.

Bourrée by J.S. Bach

In the above video, baroque dance music, there is a bit of stretching of time at ends of phrases, but the pulse stays pretty regular throughout. Notice how we might be more free with the tempo, however, in the more improvisatory baroque prelude:

Prelude by Robert de Visée

Nonetheless, even though the prelude has a bit more rubato than the bourrée, later Romantic music utilizes rubato more often and to a greater degree:

Maria Luisa by Julio Sagreras

How to use Rubato in Classical Guitar Music

But the real question is still, how do we do it? How do we use rubato in a tasteful and stylistic way and not overdo it? Let’s break it down into five steps.

Back to the metronome

Like anything, we need to learn to walk before we can run. So the best way to learn rubato is, first, to really learn to keep a strict pulse. You’ve probably heard this advice before about learning rhythms, but you really need to make friends with your metronome. The goal here is to sync up as closely as possible to the beat of the metronome. We humans have a sort of natural rubato, but the metronome does not manipulate, does not deviate: it never lies. The metronome’s pulse is bang on. So the more work you put in to syncing up with the metronome, the more regular you train your pulse to become as well.

Internalize the pulse

Once you can sync up really well with the metronome, it’s time to internalize the pulse. Here you want to keep strict time, but without the metronome. You can always turn the metronome back on to see how well you’re doing. Sometimes tapping the foot or bobbing the head (feeling the beat with the body) can help, but the ultimate goal is to feel the pulse without any external device.

Phrasing

Next, let’s start to apply a slight ritardando, slowing down, at the ends of phrases. In the Bourrée video above, you may notice Simon slows down ever so slightly on the trill at the cadence of the first section. This has a natural feeling where the music gradually slows and comes to rest for a moment.

Once you can do this convincingly while still maintaining an overall regular pulse, we can work on beginning the very next phrase. In Maria Luisa, Simon slows down at ends of a phrase but then also gradually speeds into the beginning of the next phrase to get back up to tempo.

Agogic phrasing

In both the Prelude and Maria Luisa Simon will also linger on certain notes, relishing those notes for a moment before moving forward again. These “agogic” accents punctuate phrases by drawing the listener’s attention to notes you (or sometimes the composer) wants them to pay attention to. Think of a speaker and how they may slow down and draw attention to one word by lengthening it (and so accenting it).

All the things at once

Finally, it’s time to utilize all of these elements in one piece. Here’s a great example:

Evocacion by Jose Luis Merlin

Evocacion, the first and penultimate movements of Merlin’s Suite del Recuerdo, bears the expression mark “Tempo Rubato.” So the composer expressly wants a rubato approach. This piece can thus be a nice playground to try out all of our rubato elements.

But, a word of caution

Capricho Arabe by Francisco Tarrega

We have to be careful about stretching time too much, however, as stressed in this lesson on the intro to Capricho Arabe by Tarrega. Too often we learn rubato by listening to other interpretations, how other guitarists apply rubato to the music. The problem is that, if we start from an interpretation full of rubato, we might start to build in rhythmic habits about the music. Essentially we can mislearn rhythms as a result.

So it’s always best to first start out using a strict pulse so you learn the rhythms correctly. Then you can start to apply the steps we looked at above to gradually apply rubato. This will differ depending on the style and character of the piece. Some of this will just take time to learn. Go learn more about other ways of being expressive with tempo.

But here’s a free lesson on how to first temper your understanding of the flexibility of time before you start to go too crazy with rubato.

Conclusion

We hope this deep, deep dive into the history and use of rubato on classical guitar has been useful for your own practice. What are some of your tips for learning and applying rubato? Let us know in the comments below.

Did you enjoy the lesson above? Join CGC Academy for the rest of the lesson on Capricho Arabe and so much more!

Sources to Consult:

- Pier Francesco Tosi, Opnioni de’ cantori antichi, e moderni o sieno Osservazioni sopra il canto Figurato (Bologna: Volpe, 1723); English translation: Observations on the Florid Song: or Sentiments on the Ancient and Modern Singers, 2nd ed. (London: Wilcox, 1743), trans. Johann Ernst Galliard.

- Sandra P. Rosenblum, “The Uses of Rubato in Music, Eighteenth to Twentieth Centuries,” Performance Practice Review 7, No.1 (1994): 33–53.

- Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments, ed. and trans. William J. Mitchell (New York: Norton, 1948).

- Robert Spaethling, Mozart’s Letters, Mozart’s Life: Selected Letters (New York: Norton, 2000).

Leave A Comment